I know that many resources explain this architecture, including the pivotal paper Attention Is All You Need. I wanted to write this to cement the concepts in my mind. This architecture is what is driving the current AI revolution, so it is essential to have a good grasp of the ideas.

Since its introduction in 2017, the transformer architecture has become the backbone of modern large language models (LLMs), powering breakthroughs in generative AI, reasoning, and multi-turn dialogue. For experienced software engineers, cloud architects, and machine learning practitioners, understanding not just the what but the how and why behind transformer design, scaling, and serving is now a prerequisite for building durable, model-centric platforms.

This article offers a rigorous, implementation-aware view of transformers, mapping architectural choices directly to engineering constraints and production realities.

From Recurrence and Convolution to Attention

Before transformers, sequence modeling tasks, language modeling, translation, time-series prediction, were dominated by recurrent and convolutional architectures.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and LSTMs processed tokens sequentially, updating an internal hidden state at each step. While theoretically expressive, they struggled with long-range dependencies due to vanishing and exploding gradients. Even with gating mechanisms, training was slow and memory-intensive, and the strictly sequential computation limited parallelization on modern hardware.

Convolutional approaches, such as ByteNet and WaveNet, improved parallelism by introducing locality-aware convolutions. However, they imposed fixed receptive fields and struggled to model arbitrary positional relationships across long contexts.

The breakthrough came with the paper Attention Is All You Need by Vaswani et al., which introduced the transformer. By replacing recurrence and convolution with self-attention, transformers directly modeled all pairwise token relationships, regardless of distance, while enabling complete parallel computation across sequences. Attention was no longer an auxiliary mechanism; it became the core abstraction.

Core Architectural Components

Tokenization and Embeddings

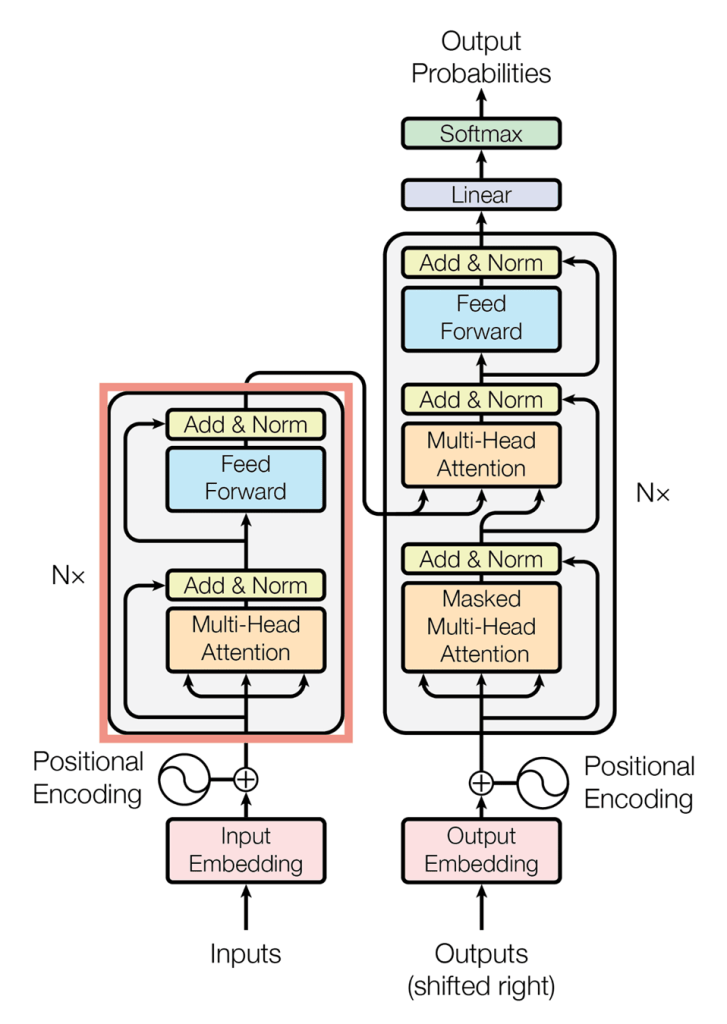

Text input is first decomposed via subword tokenization schemes such as Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or SentencePiece. Each token is mapped to a learned embedding vector. Unlike RNNs or CNNs, transformers have no inherent notion of sequence order, making positional information a first-class concern.

Early implementations used fixed sinusoidal positional encodings, injecting position-dependent sine and cosine functions into embeddings. While elegant and parameter-free, these encodings were eventually complemented, and often replaced by learned positional embeddings, which enable the model to optimize positional representations and token semantics jointly.

More recent approaches, such as Rotary Positional Embedding (RoPE) and ALiBi: Attention with Linear Biases, place explicit emphasis on scalability. RoPE rotates the query and key vectors to preserve relative positional relationships. At the same time, ALiBi introduces a linear positional bias directly into attention scores, reducing memory overhead and improving long-context generalization.

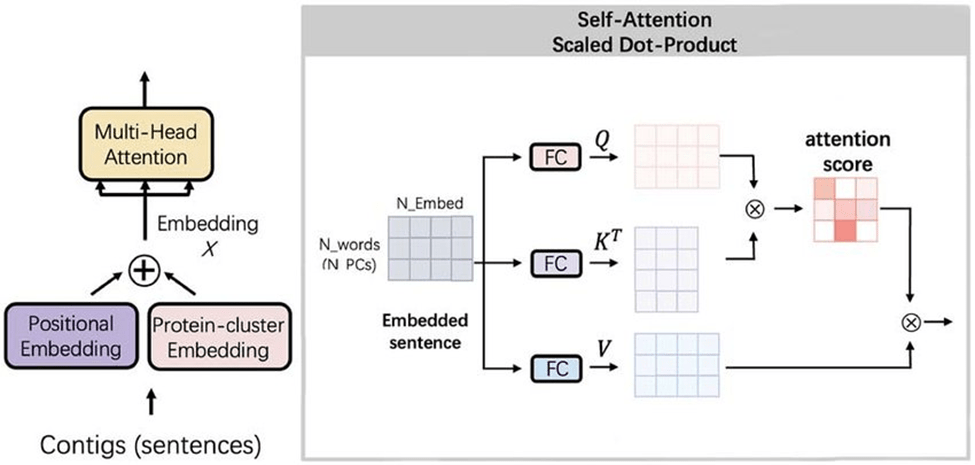

Multi-Head Self-Attention

Self-attention is the functional core of the transformer. Each token embedding is projected into query, key, and value vectors, and attention weights are computed via scaled dot-products. These weights determine how strongly each token attends to every other token in the sequence.

Multi-head attention extends this mechanism by running multiple attention operations in parallel, each with its own set of projection matrices. This allows the model to attend to different representational subspaces simultaneously, syntax, semantics, long-range dependencies, before concatenating the results and applying a final linear transformation.

The key engineering implication is cost: attention scales quadratically with sequence length. This single property has driven years of innovation in sparse attention, kernel fusion, and memory-efficient implementations.

Feed-Forward Layers, Residuals, and Normalization

Each attention block is followed by a position-wise feed-forward network, typically a two-layer MLP with GELU activations. Residual connections wrap both the attention and feed-forward sublayers, enabling stable gradient flow through deep stacks. Layer normalization standardizes activations and plays a critical role in training stability, particularly as depth and width increase.

These components may appear pedestrian, but their exact ordering, pre-norm versus post-norm, residual placement, activation choice, has measurable effects on convergence and numerical stability at scale.

Encoder and Decoder Stacks

The original transformer architecture comprises encoder and decoder stacks. Encoders attend bidirectionally across the entire input sequence and are well-suited for representation learning tasks such as classification. Decoders introduce causal masking, preventing tokens from attending to future positions and enabling autoregressive generation.

This structural asymmetry underpins nearly every modern language model design.

Modern LLM Adaptations

Decoder-Only Architectures

Most generative LLMs today, including GPT-style models, discard the encoder entirely and operate as decoder-only stacks with causal masking. This simplifies both training and inference, optimizes for next-token prediction, and improves throughput for generation workloads.

Models such as GPT and Llama 2 exemplify this approach, favoring architectural simplicity and scaling efficiency over bidirectional context.

Attention at Scale: Sparse, Flash, and Beyond

Quadratic attention complexity quickly becomes prohibitive for long sequences. Architectures like Longformer and Big Bird mitigate this by restricting attention to local windows or block-sparse patterns.

At the systems level, FlashAttention represents a different axis of optimization. By fusing attention operations into IO-aware GPU kernels, it minimizes memory reads and writes, enabling both training and inference of large models without exhausting device memory.

Scaling Laws and Architectural Trade-Offs

Empirical Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models, popularized by OpenAI, demonstrate that model performance improves predictably with increased parameters, data, and compute. However, the optimal strategy is not brute-force parameter growth. Balancing model depth and width with token throughput often yields better returns than simply increasing size.

Deeper models support hierarchical abstraction but can become harder to optimize. Wider models increase representational capacity but drive up per-token latency and memory usage. These trade-offs are architectural decisions with direct cost and performance implications.

Training Dynamics and Distributed Systems

Objectives and Optimization

Two objectives dominate language model pretraining: causal language modeling and masked language modeling. CLM directly optimizes for generation, while MLM focuses on representation learning. The choice fundamentally shapes downstream capabilities.

Optimizers such as AdamW have become standard due to their stability and decoupled weight decay, while Adafactor offers memory savings for extremely large models. Learning rate warmup, cosine decay, and careful scheduling are essential to avoid divergence during early training phases. Training Compute-Optimal Language Models

Parallelism and Sharding

Training at scale requires distributed strategies. Tensor parallelism splits individual layers across devices, pipeline parallelism staggers layer execution across micro-batches, and ZeRO-style optimizers shard optimizer state and gradients to reduce memory duplication. Frameworks such as DeepSpeed and Megatron-LM operationalize these techniques, enabling training runs that would otherwise be infeasible.

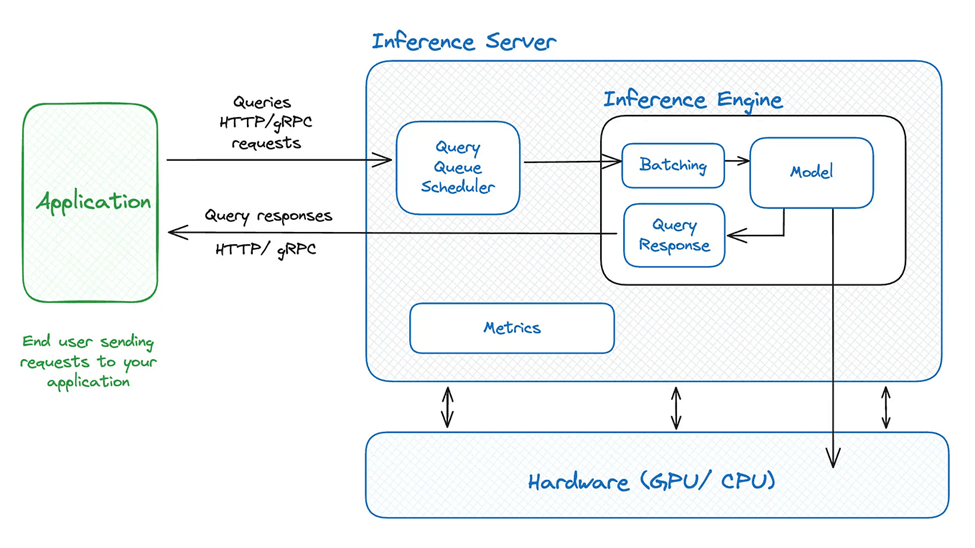

Inference, Serving, and Production Concerns

Latency and Throughput

During autoregressive inference, recomputing attention over the entire context for each token is prohibitively expensive. KV caching addresses this by storing key-value pairs from previous steps, allowing new tokens to attend only to fresh inputs. The result is dramatically reduced latency and improved throughput.

Decoding strategies further shape performance and output quality. Beam search favors determinism at a higher cost, while top-k and nucleus sampling balance creativity and coherence. Speculative decoding introduces parallelism by generating and verifying candidate continuations concurrently.

Quantization and Hardware Optimization

Quantization reduces model precision, often to INT8, INT4, or FP8, with minimal loss in accuracy. This enables faster inference and a lower memory footprint, especially when paired with post-training techniques such as GPTQ or AWQ. Modern serving engines combine quantization with fused kernels and sparsity-aware execution to maximize hardware utilization.

Governance, Observability, and Responsible Deployment

Deploying LLMs in production demands more than performance. Drift detection, hallucination monitoring, and confidence estimation are operational necessities. Logging inputs, outputs, and system metrics enables traceability and post-hoc analysis, while safety guardrails—such as PII filtering, toxicity detection, and policy enforcement—are essential for compliance.

Enterprise platforms increasingly integrate these capabilities by default. Azure AI provides observability, governance, and compliance tooling designed to support large-scale model deployment, reflecting a broader industry shift toward responsible AI operations. Responsible AI and Model Monitoring – Azure

Conclusion

Transformers are not a transient innovation, they are the product of deliberate mathematical and engineering choices optimized for scale, flexibility, and parallelism. From attention mechanisms and positional encoding to distributed training and inference optimization, every design decision carries real-world implications for cost, latency, and reliability.

As models grow larger and deployments more complex, mastery of transformer internals is no longer optional. For engineers and architects building the next generation of AI systems, understanding these foundations is essential to delivering models that are not only powerful but also scalable, safe, and production-ready.

Leave a comment